The Camera Never Lies…

(Originally written and posted to my previous blog “Quintessential Irrelevance” in March 2015. Updated Dec 2025)

The title of this post makes me itch.

Unless I have a big break, I have always been a hobbyist photographer. I’ve dabbled in journalistic, glamour, live music and events, weddings, and generally most areas of photography. My favourite subject matter, and where I spent most of time in the past, was live music photography. It’s safe to say that I know how to use my camera and have plenty of knowledge of photographic theory to get me by. And it’s for that reason that the old saying “The camera never lies” has always bothered me.

This phrase was coined in the mid to late 19th century when it was assumed that, unlike an artists canvas, the camera would record a precise image of what it was pointed at on to the plate. This was a fair assumption to make, as up until the invention of photography the only way to record someone’s image was by paying an artist to paint a portrait, and more often than not, the finished product would be shaped by how the subject wished to be perceived, and the artists own ability and interpretation, and not what the eye actually saw. Famously Oliver Cromwell, who was opposed to all forms of personal vanity, was rumoured to have countered this tradition when he allegedly asked the painter Sir Peter Lely to “Paint me as I am, warts and all”. Although whether Cromwell actually used the words “warts and all” is hotly debated by historians.

“Paint me as I am, warts and all”

Image Credit: Sir Peter Lely / Birmingham Museums Trust

Whilst many people still use “the camera never lies” in a literal sense. The assumption that the camera could not lie, and the phrase itself, has seemingly become a more ironic statement in the proceeding years, as photography has developed in to a much larger art form.

Photographic technology is always evolving, and with over a century of advancements and innovation allowing photographers to achieve a huge range of angles quickly and easily, accurately control shutter speeds and apertures, apply filters, use flash lighting and studio lighting, the lies that a photographer is able to tell become endless simply with the click of a button. For example, have you ever wondered why the sky and ocean of destinations in every holiday brochure is always a perfect rich blue? Simply add a Polarising filter and the photographer is able to achieve this without the use of any advanced photo manipulation or post processing techniques at all.

Left: Without Polarisation

Right: With a Polarisation Filter

Image Credit: PiccoloNamek / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 / GFDL

Further to in-camera manipulation; darkroom, and more recently, computer photo manipulation, have played a huge role in creating the irony of the phrase. Early darkroom techniques would involve retouching the finished product or the negatives with ink or paint, taking double-exposures wherein a plate or piece of film is exposed to two different images, splicing photos or negatives together in the darkroom, and scratching the plates or film.

Most of these techniques, and several new techniques like airbrushing, would be used right up until the invention of computer photo manipulation in the 1980’s where programs such as Paintbox, and Scitex workstations, began being used widely in the professional environment. These have been effectively replaced with more modern and versatile software and equipment that are now used both professionally and in the home, the most popular software being Adobe Photoshop. As a result “Photoshopping” is now the most commonly used term for the practice of photo manipulation, replacing it’s predecessor “Airbrushing”.

Of course the biggest contributor to the irony of the phrase that “the camera never lies”, is the photographers themselves.

“Photographers, especially amateur photographers, will tell you that the camera cannot lie. This only proves that photographers, especially amateur photographers, can; for the dry plate can fib as badly as the canvas on occasion”. – Evening News, Lincoln, Nebraska. Nov 1895

Like an eager and loyal servant, the camera will do exactly what the photographer tells it to do, and as a result it will capture the world exactly how the photographer wants it to be seen. Even without the use of any advanced photo manipulation, in each shot the photographer will imprint their own style and personality, and in many cases they may also imprint their own opinions, bias, and propaganda; and this may only take a minor adjustment such as simply changing the angle which you shoot a subject to depict them as heroic, humble, or the villain. And the most common in modern-day propaganda techniques is choosing to only tell half of the story, by shooting what you want to shoot, and not what should be shot. In doing so the photographer, without any in camera or post processing manipulation, can have a huge impact on the way in which a scene or event is portrayed and perceived.

Kevin Carter was a controversial journalistic photographer, who with three other photojournalists (nicknamed the “Bang Bang Club”), used his talent to bring light to the violence and suffering of apartheid times in South Africa during the 1980’s and early 1990’s. Carter saw horrendous suffering and violence in South Africa, and took what were often very disturbing and challenging images. He was a talented individual who unfortunately, due to being haunted by the events which he saw, took his own life in July 1994. An excerpt from his suicide note reads:

“I’m really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist…depressed…without phone…money for rent…money for child support…money for debts…money!…I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings & corpses & anger & pain…of starving or wounded children, of trigger-happy madmen, often police, of killer executioners… I have gone to join Ken if I am that lucky.”

(“Ken” refers to “Bang Bang Club” photographer Ken Oosterbroek, who died when he was shot whilst covering a gun battle with Carter in Thokoza Township outside Johannesburg in April 1994)

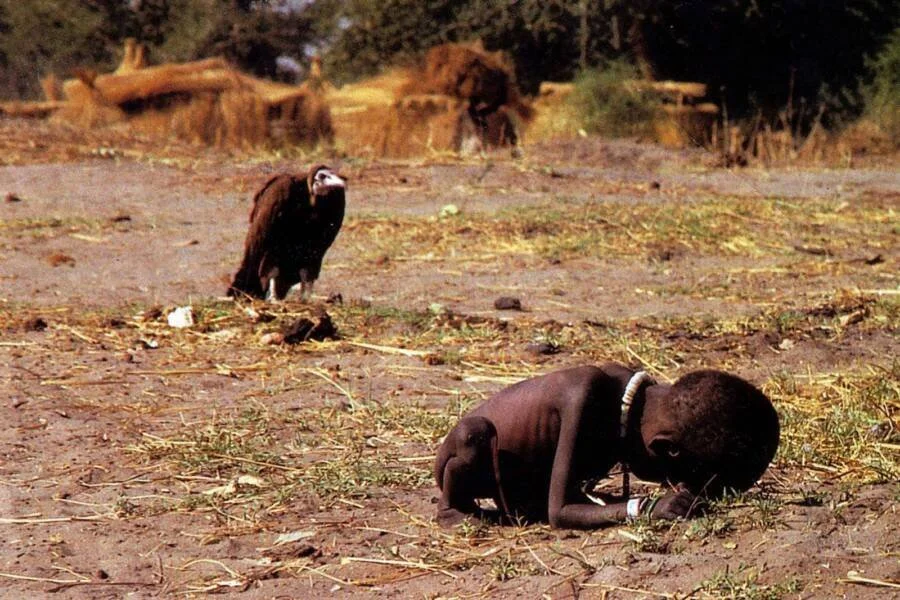

So why is any of this relevant to the phrase “the camera never lies”? Carter, as well as a talented photojournalist, was also a Pulitzer Prize winner. In 1993 he shot the famous “The Vulture and the Little Girl” photograph. The image shows a starving young child in Sudan who it appeared was being stalked by a vulture as she tried to reach a feeding center. The image is poignant. The girl, who is crying with hunger and wasting away, is seen as nothing more than the next meal to the hopeful vulture, who is seemingly patient as it waits for the child to die.

Kevin Carters “The Vulture and the Little Girl” photograph depicting a vulture watching a starving child in Sudan, 1993.

Image Credit: Kevin Carter

The picture was sold to The New York Times and appeared in the paper in March 1993, where it quickly spread internationally. However, some have criticised the image and Carter’s accounts of the events, stating that not all is as it seems.

In his book “The Boy Who Became a Postcard”, Japanese journalist and writer Akio Fujiwara included Portuguese photojournalist João Silva’s account of the circumstances in which the photograph was taken. Silva claims that the girl in the photo was one of many children in the area who had been left only for a few moments while their parents, who emerged from nearby huts, collected food from the food center, which was being distributed by the United Nation workers Carter was traveling with, only a few metres away. Carter, who had never seen a famine situation before began taking shots of all the children in the area. The Vulture, was apparently a lucky coincidence, and had actually come from a nearby manure pit. Silva states that Carter slowly, and patiently approached and took several photos ensuring both the child and vulture were in frame and in focus. Once done he chased the vulture away.

José María Luis Arenzana and Luis Davilla, two Spanish photographers who were in the same area at the time, also took several similar images, unaware of Carters photo. Like Silva’s account they also state that the location, which they too had visited, where Carter’s image was taken, was near a feeding center, and the vultures came from a manure pit nearby. They were in fact not stalking the starving children but taking advantage of vegetation in the area. They also state that by using clever photographic techniques and playing with a zoom lens and the depth of field, the vulture could potentially be 20 metres away from the child, although could still be shot as if to appear right behind her. They go on to claim the picture was nothing more than a hoax.

These criticisms could be seen as unnecessary and simply a result of jealously, after all Carter won a Pulitzer Prize and critical acclaim for his photo, and helped bring international attention to the suffering many were facing in the area at the time; but with doubts being raised as to the authenticity of the event, and with Carter’s own thoughts, feelings, and personal agenda, it’s not impossible that Carter could have taken advantage of photographic technique and coincidence, choosing to ignore the full story and in its place create his own, and as such this image could be viewed as bias and sensationalist, rather than an accurate depiction of the events in Sudan.

While Kevin Carter isn’t the only photographer that may or may not be guilty of doctoring an image for personal or political gain, the fact that this practice happens on a day-to-day basis in newspapers, magazines, and on the internet, and that even Pulitzer Prize winning images are questioned for their authenticity, it’s clear that the phrase “the camera never lies” can only ever be used in an ironic sense to ensure we’re always aware that what we see may not always be the truth. Unless of course a revision is made, after all the camera technically doesn’t lie, as it will always accurately record whatever it’s told to. In short: